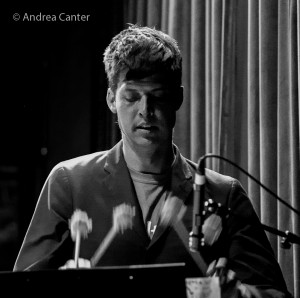

“Avant garde” jazz, or more generally “avant garde music” can be a scary label, one that can send mainstream ears scurrying for cover amid fears of harsh dissonance and incomprehensible, formless sound effects. The suggestion of “spontaneous improvisation” can generate similar discomfort — without planning, how do we prevent a train wreck? In my early years of listening to both jazz and 20th century classical music, I faced such demons and initially had to turn my ears away. I couldn’t fathom enjoying Cecil Taylor, Schoenberg or even Mingus. I credit pianist Craig Taborn with helping my ears move farther left, as his early dates with contemporary mainstream saxophonist James Carter, as well as with his own first trios, provided me with the sonic baby steps that eased me into hearing–even seeking– new sounds as his musical adventures (and mine) went farther and farther into freer unknown. Today I love Mingus, Schoenberg and other musics that are not really part of my DNA. I like new sounds. I don’t always like where they land, but I do enjoy the creative journey. As they say on NPR’s “Engines of Our Ingenuity,” I like “the way inventive minds work.” Taborn, now regarded as one of the most ingenious of his generation of keyboard artists, forms one-third of the Ches Smith Trio, joining leader/percussionist Smith and violist/violinist Mat Maneri on their debut release, The Bell. You can call it avant garde jazz, experimental chamber music, whatever. I will call it adventurous, collaborative improvisation. And genre aside, it is exquisite music.

“Avant garde” jazz, or more generally “avant garde music” can be a scary label, one that can send mainstream ears scurrying for cover amid fears of harsh dissonance and incomprehensible, formless sound effects. The suggestion of “spontaneous improvisation” can generate similar discomfort — without planning, how do we prevent a train wreck? In my early years of listening to both jazz and 20th century classical music, I faced such demons and initially had to turn my ears away. I couldn’t fathom enjoying Cecil Taylor, Schoenberg or even Mingus. I credit pianist Craig Taborn with helping my ears move farther left, as his early dates with contemporary mainstream saxophonist James Carter, as well as with his own first trios, provided me with the sonic baby steps that eased me into hearing–even seeking– new sounds as his musical adventures (and mine) went farther and farther into freer unknown. Today I love Mingus, Schoenberg and other musics that are not really part of my DNA. I like new sounds. I don’t always like where they land, but I do enjoy the creative journey. As they say on NPR’s “Engines of Our Ingenuity,” I like “the way inventive minds work.” Taborn, now regarded as one of the most ingenious of his generation of keyboard artists, forms one-third of the Ches Smith Trio, joining leader/percussionist Smith and violist/violinist Mat Maneri on their debut release, The Bell. You can call it avant garde jazz, experimental chamber music, whatever. I will call it adventurous, collaborative improvisation. And genre aside, it is exquisite music.

Coming together for one night at the 2014 New York Winter Jazz Fest, known for incubating and promoting pioneering trends in modern improvised music, the Ches Smith Trio received such accolades that their collaboration had to continue; a few months later they recorded The Bell for ECM, and found themselves back at the Winter Jazz Fest with their new release for 2016. The album is a series of minimalist soundscapes, a set of collaborative dreams with wide open spaces for each musician to explore, generating mysterious moods and musical shadows that morph from one shape into another. Officially these are eight original “compositions” from Ches Smith, but largely the music seems spontaneously improvised, each track building around a faint sketch of structure.

The opening title track suggests the direction of the whole, with gentle, dark belltones, droning keys, deep notes from viola, some strokes from Smith’s vibes–it’s very orchestral for just a trio. Taborn’s high-end crystals and repeating phrases recall his solo work on Avenging Angel as well as his trio collaborations on Chants. About two-thirds through, Smith injects some thunderclaps from timpani and the tide begins to rise, Taborn’s drone more insistent, Maneri’s strings more assertive; Smith thunders one last time before the final bell.

“Barely Invallic” feels haunted; unison lines between keys and viola, fed by Smith’s insertions, play as sound experiments but there is a unifying, underlying elegance that keeps it accessible. Smith flutters as much as thumps, Taborn and Maneri engage in melodic forays that give hints of Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and later composers. At thirteen minutes, “Isn’t It Over?” is the longest track. Taborn and Maneri seem to set themselves on different paths, yet they don’t wander far from each other and the result is harmonically rich rather than confusing. Smith builds to a more hyperkinetic segment of rolling beats to fill in the spaces left wide open by Taborn’s chord sequences and Maneri’s frenetic passages. Ultimately percussion takes center stage– a quasi bridge to the next planet, marked by Taborn’s more aggressive left-hand drone and Maneri’s probing, shifting to an almost rock-infested conversation. “I’ll See You on the Dark Side of the Earth” piles on assertive drum beats, pleading string lines, and shadowy piano. Maneri’s scratchy wanderings add a feeling of impending darkness as Smith generates metallic clatter. The trio generates increased frenzy as they slide to the finish, the intensity receding quickly amid dark tones and high-pitched sighs.

“I Think” is given a gorgeous beginning as if the musicians are sitting on an ice floe surrounded by the twinkling of the infinite night sky. Hints at a melodic theme appear, courtesy of Maneri. The exchange become more intense as they move along with a return to repeating patterns from Taborn and a rockish pulse from Smith, an eruption with a quick recession. “Wacken Open Air” has a more syncopated rhythm, like an extraterrestial swing dance with a rolling round of melodic fragments. Taborn shines here with flurries of notes that climb and fall in clusters before returning to his mezmerizing, repetitive phrases. On “It’s Always Winter Somewhere,” Taborn starts with dark up-and-down figures that become increasingly melodic; Maneri engages in sincere conversation while Smith muffles his drums, giving primacy to cymbal statements. Closing with “For Days,” the trio takes a higher energy start with Maneri furiously pushing a repeating sequence over piano drone that evolves more gently, vibes playing lushly off piano and viola.

Fans of the avant garde in jazz, classical, and improvised music will find plenty to enjoy on The Bell, and those less sure of their affinity for the sonically unexpected are likely to find themselves intrigued by the elegance and delicacy of this music, enough to take those next baby steps.